The Improbable Story of John Perkins

This is a story about John Perkins, a former carpenter’s assistant who rose through the ranks of the British Navy to become captain of a 32-gun frigate patrolling the waters of the Caribbean.

Perkins was also black. And yet this meant little to the officers and politicians who praised and promoted Perkins throughout his storied career.

Born around 1750, little is known of Perkins’ early life until his name appears in official naval records in 1775.

But he’s mentioned frequently in the years that follow. He was given command of a small schooner, acquired the nickname Jack Punch and went on to capture an incredible 315 enemy ships.

Perkins was so successful that one of Britain’s most famous admirals, George Rodney, wrote* of his exploits to the admiralty in London.

“I must therefore desire you will please represent to their Lordships, that on my arrival at Jamaica, I found Mr. Perkins lieutenant and commander of the Endeavour schooner — that he bore an excellent character, and had done great service.”

Adm. Rodney was also born poor and rose through the ranks on merit, so perhaps it’s not a surprise that he admired a black sailor whose success mirrored his own.

But how do we explain the following remarks by the governor of Jamaica, which at this time still had slaves.

By the gallant exertions of this officer some hundred vessels were taken, burnt, or destroyed, and above three thousand men added to the list of prisoners of war in favour of Britain; in short, the character and conduct of Captain Perkins were not less admired by his superior officers in Jamaica, than respected by those of the enemy.

A changing world

Why would the governor of an island with slave plantations praise a black man for wielding such power in the region?

The incongruity becomes stranger still when you consider that at the same time black slaves were subject to the whip in Jamaica, just offshore a black naval captain was regularly having his white sailors whipped as well.

In just one year while in command of the HMS Drake, Perkins ordered 14 of his 86 men to be given between 7 and 18 lashes (this wasn’t unusual for sailors at the time).

Perkins story is remarkable. But it wasn’t an accident. The late 1700s were a period of great social change in Britain as the public turned against slavery. It was officially banned on British soil in 1772, when Perkins would have been about 18, and in 1807 the British parliament would vote 283 to 16 to abolish the Atlantic slave trade.

A year later, the British navy created the West Africa Squadron to patrol the coast of West Africa and they would end up seizing about 1,600 ships and freeing 150,000 slaves.

This was the backdrop to Perkins’ rise to captain. He had remarkable skill as a pilot and fighting sailor at a time when social attitudes were changing dramatically.

And his story, while amazing, wasn’t actually that unique.

The black sheriff

At the same time Capt. Perkins was terrorizing French and Spanish shipping in the warm, blue waters of the Caribbean, a recently freed slave was sailing through these same waters on his way to England from the island of St. Kitts.

His name was Nathaniel Wells, the eldest son of a Welsh plantation owner and a slave known today only as Juggy. Just 10 years old when he moved to England, Wells would eventually marry the daughter of the Royal Chaplain to King George II and become a wealthy and important member of British society.

He was also the first black sheriff in Britain, which meant a former slave was pronouncing the guilt or innocence of white Britons. He was describedas “firm but fair.” Later he was appointed an officer in the British army and led troops against striking coal workers.

“It was then decided that a party of the cavalry, under the command of Lieutenant Wells, of Piercefield, should form a kind of advance guard, and should precede the main body by about a mile, to prevent the breaking up of the roads."

His 3,000 acre estate at Piercefield House later fell into ruin but the grounds are now home to the famous Chepstow racecourse.

Perkins and Wells weren’t alone as black men acquiring positions of power in white society at a time when much of the world was still stained with slavery.

Olaudah Equiano

Perkins would likely have heard of another British sailor at the time named Olaudah Equiano, who was kidnapped by African slavers in what is now known as southern Nigeria when he was just 11.

Sold to a British naval officer and then to another, Equiano learned to read and write while trading on the side until he earned enough money to buy his freedom. He traveled the world as a free man, visiting places as far flung as Turkey and even the Arctic before moving to London and becoming a prominent member of an abolitionist group called the Sons of Africa.

He published a widely successful autobiography in 1789 that made him a rich man before marrying Susanna Cullen and having two daughters. He died a few years later.

Ottobah Cugoano

Another member of the Sons of Africa in London at that time was Ottobah Cugoano. Captured as a slave in Ghana, he was sold to a merchant on the island of Grenada before being taken to England.

Freed by the 1772 ban on slavery, he went on to become a prominent and forceful voice for abolition who knew the poet William Blake and the Prince of Wales. His book Thoughts and Sentiments on the Evil of Slaveryis a stinging rebuke to arguments of the day that claimed slaves were treated better than European serfs. He said it was the duty of all slaves to rebel.

Freeman of York

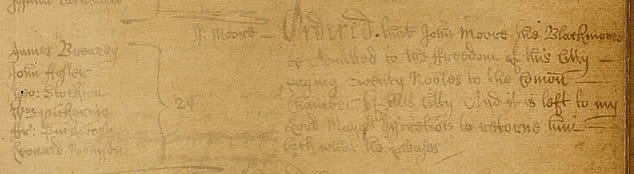

The details of history fade the further back we travel. Fewer records were kept and they’ve had more time to be lost or destroyed. But even from this misty past we can still find examples of remarkable black history, such as this barely readable document from the city of York in 1687.

It describes the appointment of John Moore as a Freeman of the city, a privilege that separated people from the serfs who were controlled by the local landowners. Freemen gained the right to bear arms and graze animals on the city’s land.

Little is known about Moore except that he was likely wealthy — and black. His entry into the Freeman’s roll says “John Moore — Blacke.”

Progress never moves in a straight line. It leaps forward and then falls back.

But the emergence of people like Moore, and Capt. John Perkins the naval hero, and Nathaniel Wells the sheriff are those moments when we do leap forward. They shatter conventions and cut a clearer path for those that follow.

Their lives made history, one improbable story at a time.